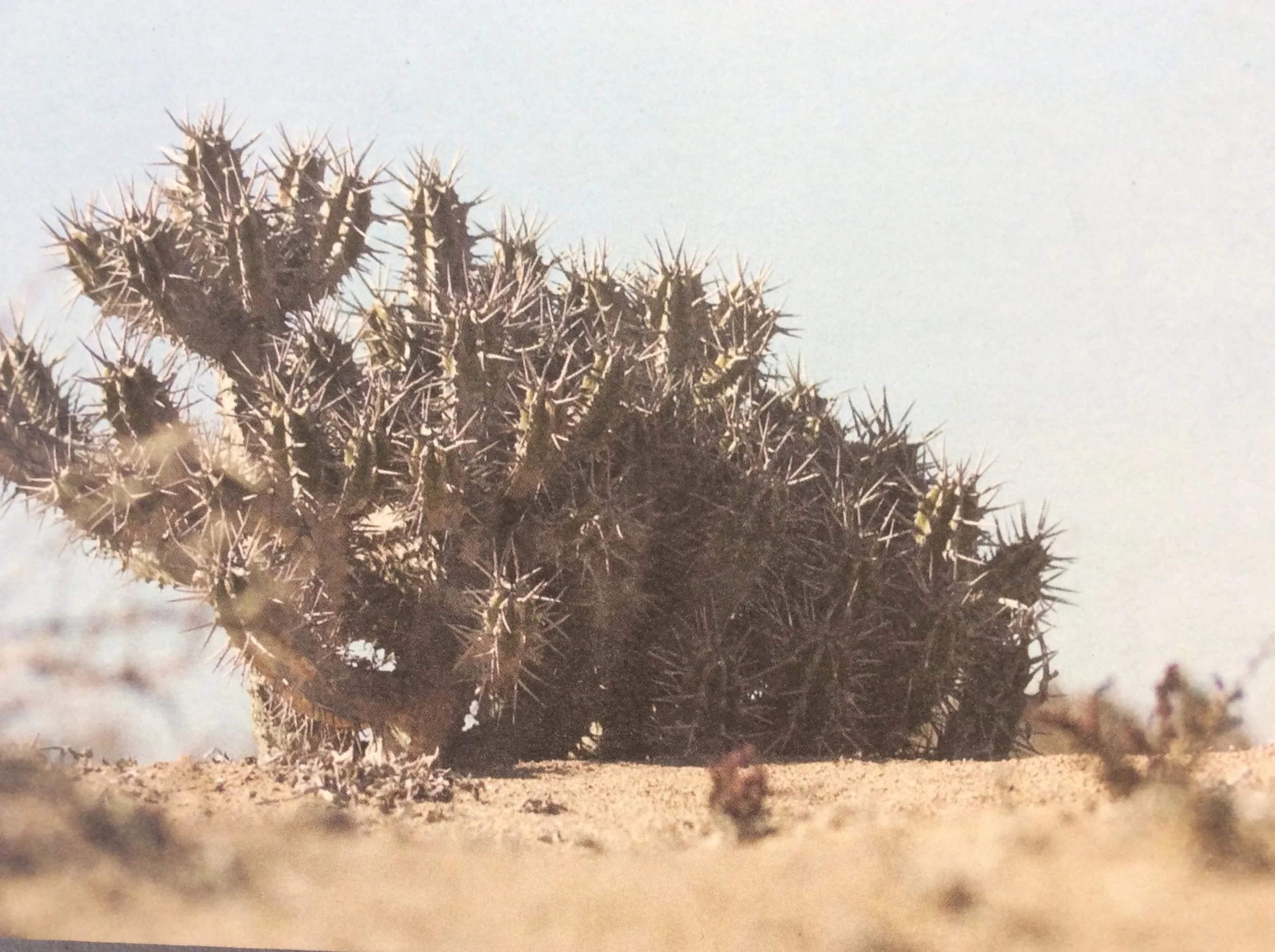

Achayef, Abdessamad El Mountassir, 2018, video still, copyright the artist, IMéRA and Le Cube

The ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) gallery in Berlin-Mitte has undertaken a three-year transdisciplinary project, Untie to Tie, that addresses colonial legacies, movement, migration and environment. I recently visited the current exhibition, Invisible, and two works were especially evocative for me.

Abdessamad El Montassir’s film Achayef takes us to the part of the Sahara where both he and his friend Weld Sidi spent their early childhood years. We see Weld Sidi walking in the desert as we hear the story of his mother, Khadija, who—as we learn—was deeply traumatized by events that forced her to leave her Saharan home around 1975. The events are not specified, not categorized even, and although Khadija refers to these events (we hear her voice and see her hands and her body seated on the floor, but we do not see her face), she says only that she had to leave and that she cannot describe what happened. As viewers we become watchful and wary, our reactions perhaps corresponding in some small degree to those of the child who has carried the story, in all its incomprehensibility, in the body. This is one kind of invisibility with which the exhibit as a whole is preoccupied — perceptions that are, in the words of the curator Alya Sebti, “beyond the margins of the visible,” in this case presumably the unseen is the war in the Western Sahara. But in this film we do sense something of the invisible, and we are then led into the more familiar (to many of us) territory of scientific discussion, first by a botanist who talks to us about the daghmon plant that once had leaves but turned its leaves into thorns in response to environmental conditions, another scientist who discusses human trauma and its effect on the limbic system. This transition is a powerful and at the same time, gentle strategy that prevents us from exoticizing or dismissing the main story as having to do with the other.

In One story amongst many others, Zainab Andalibe presents a web fashioned out of thread—two meters in diameter, dense at its center yet sparse overall—and displaying a luminous palette. The web is accompanied by a written dialogue, in which one voice, perhaps that of the artist, perhaps not, describes to another a meditative practice of walking.

“Yes, I like to walk. It is as if I connect to the divine, as if I am praying.”

“You pray?”

“No, I walk, I like to walk for hours . . . “

As the dialogue continues, we are given to understand that the walking practice is generative of the web; the thread marks the walking and changes color when the walker encounters others. I was drawn to the web because of its spare beauty. What is intriguing beyond that is the notion of a ritual delineated through artistic practice, connecting the sensorial with the spiritual. The work is an instance in which the material and the conceptual meet in an uncanny way—to be sensed and not explained.

— Carolyn Prescott