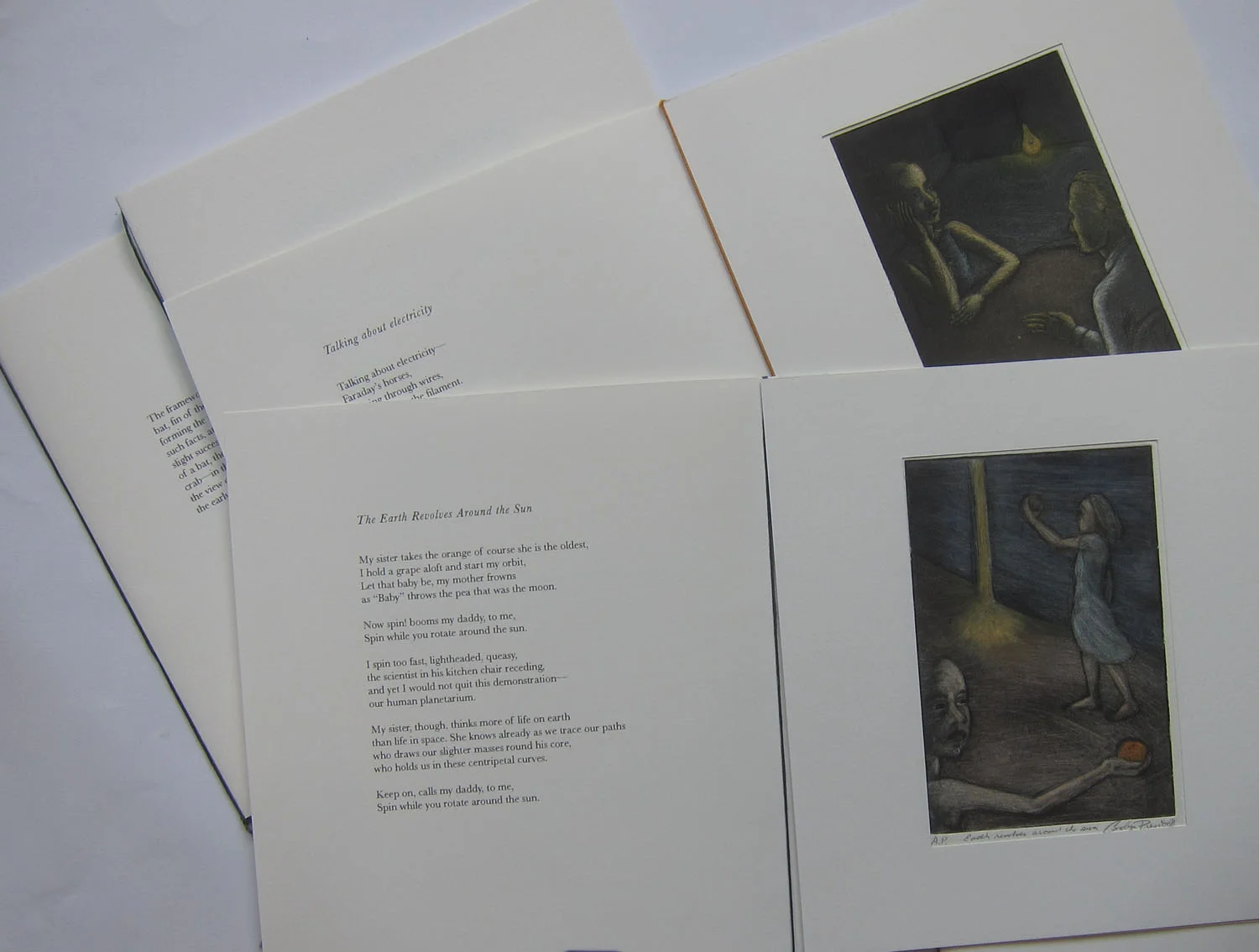

Science in the Family, artist’s book with six hand colored etchings, 6 poems and prose pieces; 2016; limited edition

The following excerpt is the framing essay from the artist’s book, Science in the Family

Transmitting Wonder

To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling, is at the center of true religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I belong in the ranks of devoutly religious men.

– Albert Einstein, in Living Philosophies: The Reflections of Some Eminent Men and Women of Our Time

Certain scientific ideas and principles have been with me for almost as long as I can remember. These ways of knowing the world—through atoms, molecules, cells, the electromagnetic spectrum, Darwin’s theory—all began for me with my father’s impassioned explanations.

My father Charles was an unlikely teacher, given his eighth grade education and his occupations as a carpenter, and later on, construction supervisor. He had grown up in the swampy lowlands east of Columbia, South Carolina, under the religious tyranny of his mother, a fervent Baptist intent on finding the path of righteousness, pointing out the sins of others (and not sparing the rod) and anticipating the glory of the “end days.” This strict fundamentalism did not appear to have taken hold of my father in his earlier years, but when he reached his late twenties, not long after I was born, he began taking our family to the fire and brimstone Baptist church, and during a period of financial stress, he came to believe that he was being called to the ministry by God. In the ensuing altered state that he attributed to the Holy Spirit, he followed my mother around the house, reciting long Biblical passages from memory. He soon quit his job to occupy himself solely with religious questions.

His obsessive zeal was eventually interrupted by doubt, triggered in part—as he explained to us—by my sister’s nightmares of “burning fingers,” which began after one particularly vivid hellfire sermon. What kind of religion is this, my father wondered, to so frighten a small child? Books lent by a lawyer whose house library he was remodeling provided a catalyst for his thinking: Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy, and Faiths, Cults, and Sects in America were two that made a strong impresssion. Later on he read Darwin and Freud. The crisis of faith led eventually to his psychiatric hospitalization and our family’s move to North Carolina, a state away from the direct influence of my grandmother.

My father’s story was not one of simple triumph of reason over dogma, however. The journey from belief in a personal god (a phrase I first heard from him) to a scientific view of life brought estrangement from much of his original family and the loneliness of a working class man who had few opportunities to discuss ideas with others. He often drank excessively and he was depressed for months at a time, straining our family life and leaving our mother Helena to carry us through periods of joblessness and a later round of hospitalization. A primary image of him from childhood: he is home from work and sitting at the table hunched over a book; he does not speak much, he does not notice me there.

Despite his often withdrawn demeanor, as soon as I was old enough to form questions about the world, he began to answer them enthusiastically. His delivery was charismatic, with all the rhetorical flourish and timing of a southern Baptist sermon even if the subject was electricity, germ theory, or covalent bonding.

While my father’s scientific understanding cannot have been deep, he conveyed it honestly as an open framework, with gaps and possible errors (of his own in the telling as well as of the scientists themselves), yet to be probed and filled in. For my part, I did not always grasp his explanations in their entirety. My mother (meaning to help me out of my position as a captive audience of one once my sisters had fled the room in dread of “another lecture”) would sometimes interject, “enough, Charles, she can’t understand all that.” Determined to live up to expectations, I would, of course, immediately claim to understand “everything!”

For the kitchen table lectures undoubtedly served many purposes: they provided attention that I craved and a balm on the psychic wounds inflicted by my father’s moods under the influence. Not infrequently I saw them as a way to control his behavior while he was intoxicated. The transmission of knowledge, then, was a thrilling but uneasy process, fraught with the fundamental contradictions and insecurities of our family life. Nevertheless, my father imparted to me many core principles and theories of science, infused with great religious feeling, that is, with a sense of awe and delight for what really exists. And so he nourished in me a certain alertness in the world, a will to notice, a desire to understand.

— Carolyn Prescott