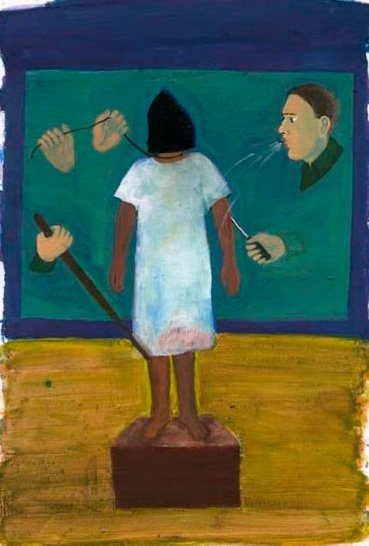

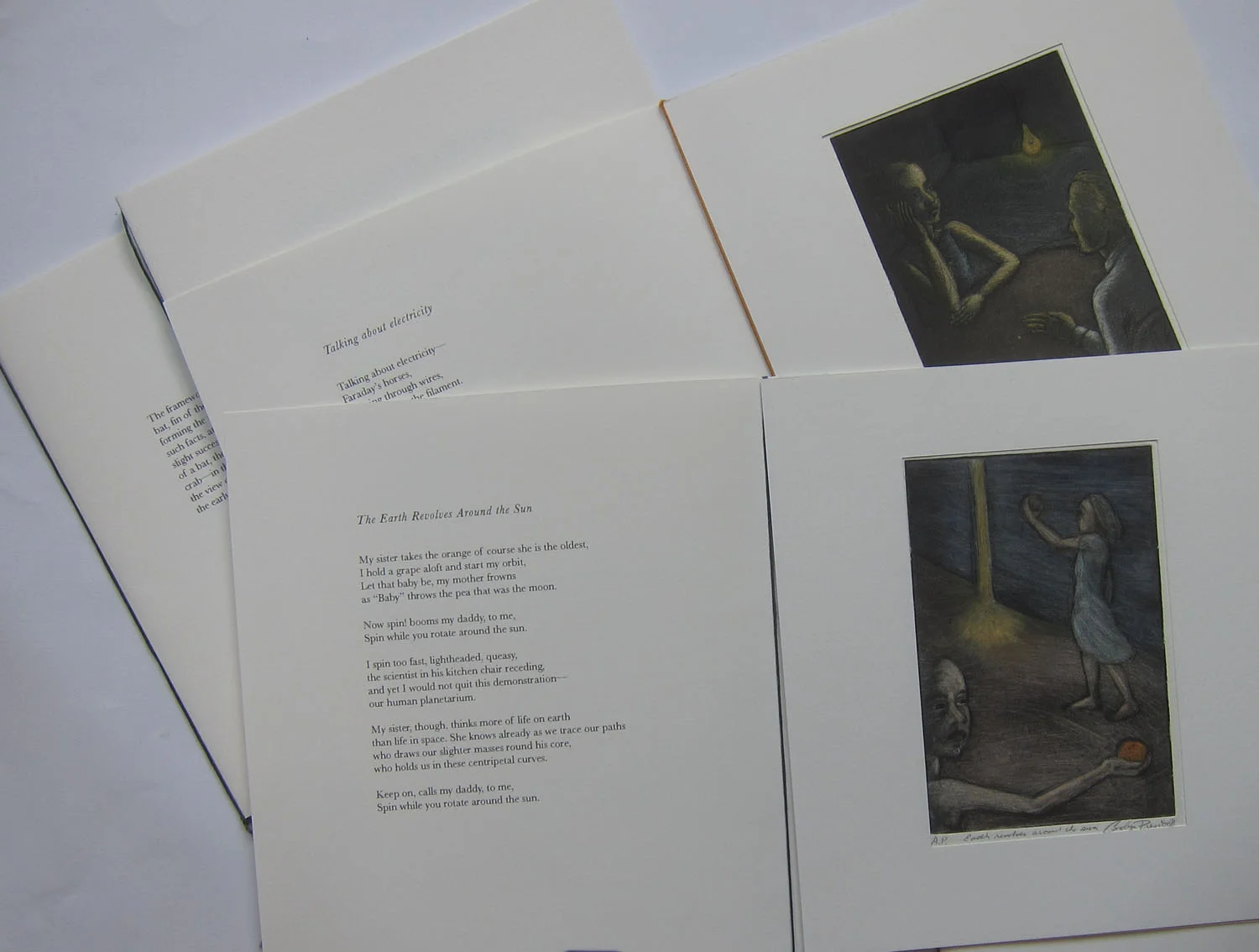

The Mocking of Christ at Abu Ghraib, Carolyn Prescott 2004

September 11, 2021 marked 20 years since suicide attacks targeting the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C were carried out by militant Islamic extremists, resulting in the death of almost 3,000 people. The anniversary of 9-1l has prompted remembrances of the attacks as well as their consequences: the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the detention of thousands of suspected terrorists in Guantanamo and secret sites in other countries, and the use of torture in the interrogation of suspects. Early on, the Bush administration declared the suspects to be “unlawful combatants” and thus held them outside the jurisdiction of U.S. courts and without rights under the Geneva Conventions. At Abu Ghraib prison, located about 20 miles from Bagdad, members of the U.S. Army and the CIA committed war crimes against detainees, including physical and sexual abuse, torture, and rape. In 2004 CBS News published photographs of the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, and—as legal memoranda exchanged among members of the Bush administration showed—the human rights violations at Abu Ghraib were not the result of a few individuals gone out of control, but rather part of a strategy intended to evade international laws and norms.

I don’t remember when I first saw the photographs of torture at Abu Ghraib, but the image of the hooded prisoner standing on a box with wires attached to his fingers was fixed in memory when, later that year, I was fortunate to see the frescoes painted around 1441 by the Dominican Friar known in English as Fra Angelico, at San Marco in Florence. Among them was the “Mocking of Christ with the Virgin and Saint Dominic,” which depicts Christ blindfolded, beaten with a stick, and spat upon. The two images—the “hooded man” at Abu Ghraib and the blindfolded Christ on the wall at San Marco—were linked in my mind almost immediately.

The Mocking of Christ with the Virgin and Saint Dominic, fresco by Fra Angelico, San Marco, 1441-2

Fra Angelico painted the Mocking of Christ on the wall of Cell 7 of the monastery of San Marco not as Matthew described it in Chapter 27 of his gospel: “Then the soldiers of the governor took Jesus into the common hall, and gathered unto him the whole band of soldiers. And they stripped him, and put on him a scarlet robe. And when they had platted a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head, and a reed in his right hand: and they bowed the knee before him, and mocked him, saying, Hail, King of the Jews! And they spit upon him, and took the reed, and smote him on the head.And after that they had mocked him, they took the robe off from him, and put his own raiment on him, and led him away to crucify him.” Instead of a dramatic scene, Fra Angelico created a tranquil symmetrical composition, a stage of sorts but a very quiet one. The colours resonate calm even as they serve as spiritual signifiers (green for the resurrection, red for the blood Christ shed, for example). The gestures and facial expressions of the figures depicted—Saint Dominic, the Virgin, and Jesus himself—convey a deep and preternatural endurance. The perpetrators are represented primarily by disembodied hands: one hand holds a stick, others appear ready to strike; one soldier only is portrayed as a head in profile, as he spits and doffs his hat derisively.

The torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib and other “black sites,” as evidenced in videos and testimony, was brutal and terrifying, intended not only to injure but also to humiliate the prisoners, to attack and mock their religious faith, and to destroy any sense of dignity or agency. The photographs of these acts are almost unbearable to see. To reproduce them in a painting seemed not only pointless but in some way an amplification of the wrongdoing. The iconography of Fra Angelico immediately offered a way to refer to these acts without adding to the harm done by members of the U.S. military, to call attention to what happened but not to re-enact it. However, when I made the small gouache painting of the “hooded man” of Abu Ghraib in 2004, I did so intuitively rather than analytically. Nor was I motivated by religion, as I am not a member (not even a lurking one) of any religious group. However, I was exposed to the Judeo-Christian tradition and to Bible verses throughout my schooling in the southern U.S. and also by my parents, who, while not believers, were certainly bearers of many principles and much poetry from their own religious backgrounds.

The link between Fra Angelico’s painting and the image from Abu Ghraib was strengthened for me by the memory of another Bible verse learned long ago, Matthew 25, verse 40: “And the King shall answer and say to them, Truly I say to you, Inasmuch as you have done it to one of the least of these my brothers, you have done it to me.” The verse actually refers to acts of charity or the lack thereof, but it came to my mind as applicable not only to sins of omission such as failing to feed the hungry, but also to sins of commission such as acts of abuse or violence, like those carried out against the prisoners at Abu Ghraib. The verse places Christ on a level with the ignored or persecuted, “the least of these.” It does not speak of what is deserved or whether someone is guilty or innocent of the crime of which they are suspected. This sense of equality is presumably not based on someone’s ability or goodness or wealth, and certainly not on their religious faith, but on the condition of being a human being among other human beings in the world. And whatever its antecedents, it is not too much to call it a principle of political equality. In the last century, in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, this idea helped to bring representatives from 196 countries to a consensus on the Geneva Conventions, defining among other things, the basic rights of wartime prisoners.